This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

In recent years, many corporations, including BP, Target and Volkswagen, have been prosecuted for various scandals and suffered financial and reputational damage for inflicting harm on their respective employees, customers, shareholders and communities. While these companies come from a wide range of industries that each face unique challenges, these cases all have a common thread: Ultimately, their failures can be attributed to poor governance and risk management and an inability to identify their root-cause risks. By acknowledging this problem and taking an enterprise-wide approach to risk management, however, other organizations can avoid similar scandals and costly litigation.

Identifying Root-Cause Risks

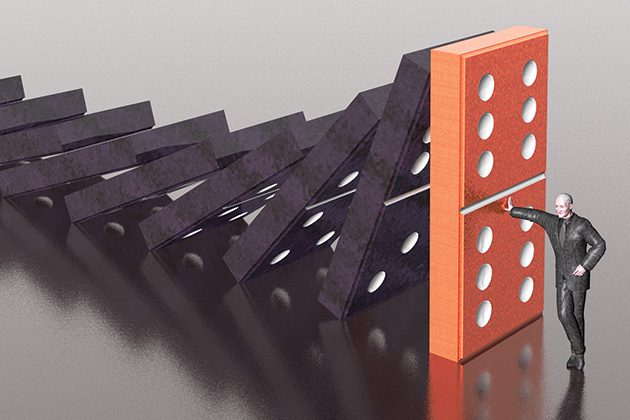

The common problem in most corporate scandals is that the relevant root-cause risks were not identified or mitigated across the enterprise. Instead, organizations addressed the symptoms of these risks as they occurred, which was often too late, and frequently placed blame on one department or group of employees, leaving the organization vulnerable to failures that stem from the same systemic issue. To properly identify root-cause risk, organizations need an effective enterprise risk management program.

Every lawsuit related to risk management failure boils down to negligence—not having the systems and processes in place to properly take action on risks known by someone in the organization.

ERM is based on the recognition that every business is made up of interconnected parts. Because these parts are interconnected, it stands to reason that the risks associated with each part, or business area, are also interconnected. In order to prevent one business area from suffering from the same underlying risk as another, ERM helps corporations identify and mitigate root-cause risks across the enterprise. By identifying these risks, businesses can anticipate what lies ahead, allocate resources efficiently, prevent failures and ensure business performance, which includes maintaining a sound reputation.

The first step in any successful ERM program is involving process-owners— the front-line managers. While the board expects the risk manager to gather and report on risk information, the risk manager cannot always access the necessary information easily. But it is already being collected within different areas of the organization by different process-owners. Being on the front lines, process-owners are the most familiar with the daily risks to the organization, making them the best source of accurate information concerning the most significant operational risks.

ERM collates the knowledge that process-owners hold by building information connections among all areas of the organization. The objective risk assessments inherent to an ERM approach are the best way to collect, centralize and leverage this information. By engaging process-owners in these risk assessments, risk managers ensure that the most accurate and current information is being used to identify and mitigate operational risks.

Failures in risk management often happen when the root cause of the risk was known at the lower levels of the enterprise but not at the higher levels where resources are approved and priorities are set. This ignorance, however, is not a valid excuse—it is negligence. Every lawsuit related to risk management failure boils down to negligence—not having the systems and processes in place to properly take action on risks known by someone in the organization.

A closer look at the scandals at Wells Fargo and General Motors further demonstrates the impact of poor enterprise risk management and how improvements in root-cause risk identification can help avoid future litigation and penalties.

Wells Fargo

Within the past year, Wells Fargo has made headlines with three scandals. First, there was the infamous cross-selling account fraud scandal. Then, the bank suffered a data breach, which was quickly followed by an auto loan scandal. In examining these scandals, it seems that their failure to mitigate a root-cause risk has been at the core of their problems.

In 2013, rumors began circulating that, in order to meet aggressive daily cross-selling targets that required the sale of multiple products to existing customers, Wells Fargo employees had been opening new accounts and issuing debit or credit cards without customers’ knowledge. As we now know, two million false accounts were created this way over the course of five years.

The bank asserted that the fault lay with their front-line employees’ unethical behavior amid a high-pressure sales culture. Indeed, more than 5,300 front-line employees were fired as a result of the scandal and CEO John Stumpf resigned.

According to Richard Cordray, director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the bank failed “to monitor its program carefully, allowing thousands of employees to game the system and inflate their sales figures to meet their sales targets.”

There is nothing inherently wrong with ambitious sales goals, as long as there are systems in place to ensure employees are not in the position to choose between their own financial security and customers’ well-being. Employees tasked with meeting these high-pressure sales targets should not have been the same employees in charge of opening new accounts, and should not have had the administrative rights to do so.

If this conflict had been identified and controls put in place to ensure that such duties fell to employees who had no personal stake in the creation of accounts, then there would have been no incentive to create them. The bank would therefore have avoided this reputation-ruining scandal and the resulting $185 million fine—the highest fine levied by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau since it began operation in 2011.

After a six-month investigation into the scandal, the bank’s board of directors found ineffective governance structures and poor risk management processes were at the heart of the problem. But even after identifying these root-cause factors, the Wells Fargo board did very little to materially change their operations, culture and leadership in a way that would better protect employees, customers and shareholders.

Failures related to these same root-cause issues also led to scandals in other business areas. In July 2017, Wells Fargo accidentally leaked the personally identifiable information from more than 50,000 accounts, including names, Social Security numbers and financial details of some of its wealthiest clients. The data had been shared as part of the discovery process in a legal dispute between two former employees and was provided without a protective order or confidentiality agreement between the parties.

As with the cross-selling scandal, Wells Fargo had not implemented effective governance procedures that would have flagged the fact that their representation should not have had access rights and duties to obtain or even view records containing personally identifiable information.

In the same month, Wells Fargo admitted it had charged 800,000 customers for collateral protection insurance they did not need. The added cost to customers’ premiums caused 274,000 customers to default on their loan payments and resulted in the wrongful repossession of 25,000 vehicles. In August, the bank began refunding customers the $80 million they were wrongfully charged.

After the news broke, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer said, “This is a full-blown scandal—again. It’s unbelievable, outrageous, sad, and yet quintessential Wells Fargo.” Once again, the root cause of this scandal was tantalizingly similar to the risk management failure in their cross-selling scandal.

In creating a cross-selling program and offering collateral protection products, Wells Fargo failed to identify and control the risks introduced by these new processes. Before any company implements a policy, it is imperative that, as part of a robust ERM structure, it performs objective risk assessments on the processes and procedures involved to uncover any potential risks before they materialize.

General Motors

A few years ago, General Motors suffered one of the worst automotive safety scandals in history. Unlike Wells Fargo, however, GM has not suffered subsequent scandals, perhaps because they successfully identified a root-cause risk and took steps to improve their risk management efforts.

In 2014, GM initially recalled 800,000 vehicles due to faulty ignition switches. Over time, the number recalled swelled to 30 million. The recalls—or more accurately, the accidents that led to the recalls—resulted in tragic deaths, multiple lawsuits and severe financial penalties.

In September 2015, GM entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice in which the company admitted that, “from in or about the spring of 2012 through in or about February 2014, GM failed to disclose a deadly safety defect to its U.S. regulator.”

As part of the agreement, GM agreed to forfeit $900 million. The company also gave $600 million in compensation to surviving victims of accidents resulting from the faulty ignition switch, and paid $35 million in fines to the U.S. Department of Transportation for delays in recalling cars that potentially had the deadly defect.

As is evident from GM’s statement, the lawsuits and penalties were not a result of faulty ignition switches themselves, but the company’s failure to disclose the safety issue. Therefore, it would be wrong to view this as a failure of a single department such as manufacturing. Rather, it reflects a failure to properly manage risk.

As a motor vehicle company, GM is obligated to notify the Department of Transportation within five business days after finding a safety defect. A lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court in Manhattan alleged that GM knew about the faulty switches in 2001, but did not recall any of its cars until 2014. By failing to escalate safety concerns in a timely manner, GM committed extreme negligence.

ERM is designed to keep all parties across the organization, from the front lines to the board to regulators, apprised of these kinds of problems as they become evident. Unfortunately, GM failed to implement such a program, ultimately leading to a tragic and costly scandal.

It appears that GM has since taken actionable steps towards an effective ERM program and improved risk culture, however. In April 2014, the automotive company announced its Speak Up for Safety program to recognize employees for ideas that make vehicles safer, and for speaking up when they see something that could impact customer safety. CEO Mary Barra also acknowledged that issue reports are only effective if there is follow-up, so the Global Vehicle Safety Group will now be accountable for taking action on a reported problem within a prescribed time period.

These procedures seem to be working so far. In May 2016, for example, GM received a report through the Speak Up for Safety program that detailed a crash involving a 2014 Chevrolet Silverado truck in which the driver’s front airbag was not deployed. Shortly thereafter, GM recalled all vehicles that could potentially house the defect, and by September, GM had identified the problem and advised all owners of these vehicles to visit their dealers for repairs.

Understanding the Risks

GM was aware of the defect 13 years before disclosing it, and Wells Fargo created a system that allowed employees to open millions of false accounts over the course of five years. Had GM and Wells Fargo provided front-line managers with the tools to identify the risks associated with their respective processes, risk managers may have been able to assess, mitigate and monitor them before they materialized into scandals and lawsuits.

It is up to the board, senior management and risk managers alike to implement an ERM program to help access that knowledge and make connections among the information being collected across the organization.

Even if prevention is not possible and a scandal does occur, corporations with well-documented ERM programs may still be able to avoid punitive penalties and litigation. The failure of management to disclose the risks involved in a program or activity—whether knowingly or unknowingly—is a large part of determining negligence. Therefore, it is important to be able to demonstrate that management is actively trying to understand risk on the front lines. In the event of a crisis, organizations have a particular incentive to implement ERM in order to benefit from federal sentencing guidelines, which offer relief from negligence claims for individuals and organizations if they can provide evidence of effective risk management.

Front-line employees are extremely knowledgeable about the processes they oversee. They know the risks they face daily. It is up to the board, senior management and risk managers alike to implement an ERM program to help access that knowledge and make connections among the information being collected across the organization, and to leverage this information to make informed decisions that will help achieve the company’s goals.

The traditional reaction to scandals—that is, hiring lawyers to mitigate the fallout after a disaster occurs—is not enough. In 2010, the Securities and Exchange Commission published a disclosure enhancements proxy that gives corporations two options when dealing with risk: 1) adopt an effective risk management program, or 2) disclose the ineffectiveness of their processes. Maintaining ineffective risk management tools without disclosure is considered negligence and can result in costly litigation.

Risk management must extend across the organization to involve individual process-owners, the board of directors and risk managers. Process-owners can use their expertise and proximity to operations to identify the most significant risks. When the board requires risk officers to report on risk assessments, mitigation and monitoring, and internal audit to report on ERM process effectiveness, they can ensure that operations are in line with strategic objectives. Risk managers are the bridge between the hands-on expertise of process-owners and the strategic expertise of the board. Ensuring that all sides are on the same page requires risk assessments and aggregation of data, followed by forward-looking, dynamic reporting.

While Wells Fargo and GM have survived their respective scandals, they are still struggling to regain the trust of shareholders and customers. The financial penalties GM and Wells Fargo paid are merely drops in the bucket compared to their revenue streams—it is the loss of market value and brand reputation that they will spend years fighting to overcome.

ERM is therefore not only a legal and moral obligation, but a method of preserving a corporation’s reputation and achieving its strategic objectives.