This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

The COVID-19

pandemic has forced educators and risk professionals to rethink school

operations to protect the safety

and health of students, faculty and staff.

In March 2020, governors in 42 U.S. states imposed restrictions on residents’ movement as COVID-19 spread across the country. Even before states began issuing stay-at-home mandates, colleges and universities were canceling classroom instruction and shutting down campuses. Some were responding to students or faculty testing positive for COVID-19 while others were attempting to stay ahead of any potential outbreak.

Soon, K-12 schools

were emptying classrooms and either canceling the school year or moving classes

online. Public and private schools alike were forced to find alternate ways to

reach a student body without universally reliable access to the internet.

Educators in the United States are hardly alone in facing this situation—UNESCO

reported that school closures have impacted 60% of the world’s students, with

over 100 countries shutting schools nationwide due to the pandemic.

As the new school

year begins to ramp up, academic institutions have been tasked with determining

how to deliver education and other much-needed services to their students amid

the ongoing pandemic. Administrators and educators must decide whether to open

schools for classroom instruction or beef up technology and conduct online

classes, be it for the short or long term.

Whatever each

institution’s decision, education will likely look nothing like it did last

year. Classrooms are now potential vectors for the virus to spread among

students, faculty and staff alike, and campuses represent potential epicenters

of future outbreaks.

Some educational

institutions must also rethink what they can do to accommodate student safety

within their current buildings. Many must confront infrastructure limitations,

outdated equipment and lack of funding to make the necessary changes to meet

best practice guidelines like ensuring physical distancing. As the entire

academic experience is being revamped and reframed around a global pandemic,

many uncertainties still loom.

Educators and

administrators have had to prepare to bring students back to class in this

extremely challenging environment. Evolving science, changing federal

government decisions, and conflicting state and local mandates have created a

landscape that is constantly in flux, and risk professionals at schools have

had to develop, amend or scrap plans on the fly to keep up. Additionally, even

if schools and campuses reopen, they must be prepared for rapid changes that

could mean they must shutter again.

Trickle-Down Confusion

Whether schools open

now or later, preparing classrooms for students to return means mitigating

health risks above all else. As administrators and risk professionals tackle

when and how to resume on-campus operations, health and safety questions should

be considered at the regional level. “You want to look at what public health

officials and the local and state governments are saying,” said Melanie

Bennett, risk management counsel at United Educators. “Are they recommending

that schools reopen in your area? That is the absolute starting point.”

Yet even answering

that question has been a difficult task. Political infighting and conflicting

priorities have resulted in upheaval at most levels of government. In Georgia,

the governor recently sued Atlanta officials for mandating mask use, claiming

that city officials were defying state-level executive orders by requiring

masks use. In Iowa, mayors defied the governor’s orders and mandated public

mask use. Despite the pandemic affecting the entire U.S. population, some

politicians have drawn partisan lines around these issues, turning public

health into political spectacle.

Institutions are

trying to create sound reopening and safety plans, but changes at the

governmental level have been swift and often contradictory. “Things can change

literally overnight with decisions from the county that you have to react to or

state decisions,” said Samuel Florio, director of risk management and

compliance for Santa Clara University. “It’s unlike any other risk management

scenario that I’ve been involved in.”

This has forced many

institutions to quickly adapt and revamp their plans. “You have to be nimble

and be able to react, and realize that the decision you’re making right now

could be completely different in 12 hours,” Florio said. In July, for example,

the Trump administration announced plans to revoke visas for international

students not attending in-person classes, such as those enrolled at

universities that moved courses online. Universities had to scramble to figure

out how to support students facing visa uncertainties and how to facilitate

having some return to campus if necessary to stay in the country. Less than a

week later, the government reversed course on these proposed restrictions.

Preparing to Reopen

After assessing the

legality of returning to the classroom, the next step is determining when it

will be safe to do so. What that entails will differ for each institution. The

developing nature of the pandemic makes it extremely difficult to create a risk

management plan that encompasses all of the most up-to-date information.

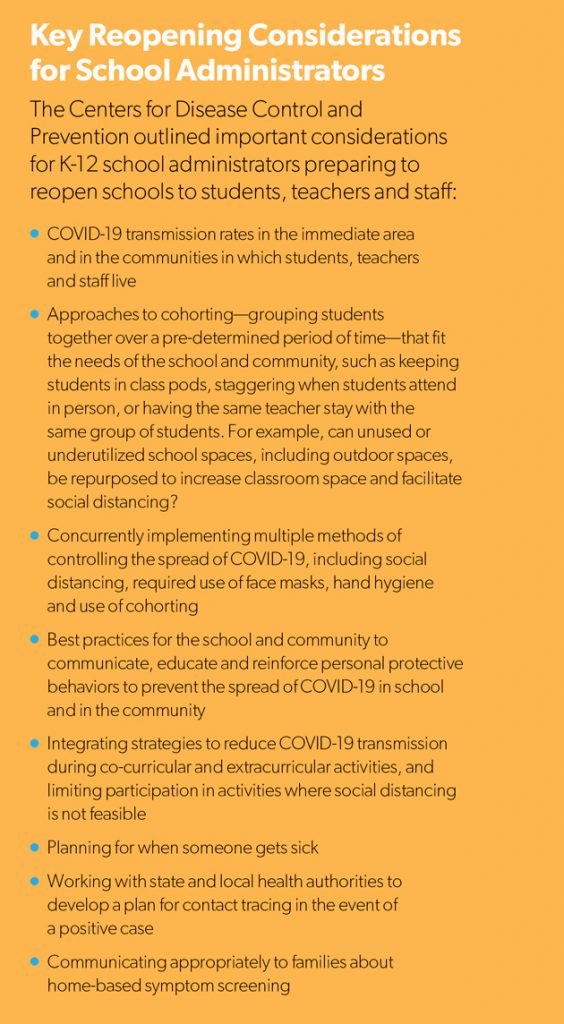

Start by following

CDC guidelines and information coming from entities such as the National

Governors Association, advised Cole Clark, managing director of higher education

for Deloitte. He suggested that institutions build a plan “that is flexible,

that can be changed and molded as conditions and information change, and that

has a set of risk-based triggers for a return to campus.”

According to Dorothy

Gjerdrum, senior managing director of Gallagher’s public sector practice, that

plan should also answer certain key

questions. “What are you going to do to prepare facilities, keep physical

distancing, and make sure you are in alignment with state laws or local

ordinances? How do you prepare your people to go back? How will you keep them

safe once they are there? Also, you need look at any potential issues around

supply chain for providing necessary materials,” she said.

When schools do

open, institutions will need to communicate each step of the process. “Whatever

schools are putting into their policies, they should all make sure that they

are providing training and education for everyone on the new policies and

procedures,” Bennett said.

That includes

training teachers and educating students and parents about available

instruction options. Steven C. Holland, chief risk officer at the University of

Arizona, said his institution has planned four teaching modalities. Level one

is face-to-face instruction, level two is a hybrid of face-to-face and online

components, level three is synchronous (or live-streaming) instruction, and

level four is asynchronous (or recorded) instruction.

Hybrid and online

configurations have created the most logistical challenges for institutions. When

the initial pivot was required in March, many institutions had to overcome

infrastructure shortcomings in real time. Fall may bring better clarity and

preparation. “The summer months allowed schools to evaluate the results from

the spring and further improve their infrastructure in anticipation of the

potential need for distance learning in the fall,” Florio said. That includes

supporting students around the world. For example, a number of colleges and

universities are adopting synchronous and asynchronous learning modules to help

reach students in different time zones.

On college campuses,

schools are making investments in technology that will improve internet access

and enhance cybersecurity infrastructure and procedures. Campuses that are

limiting available housing due to social distancing concerns are also creating

more spaces with internet access that can accommodate a limited number of

students, such as areas within libraries and student unions. “Further, since

outdoor activity seems to result in limited virus transmission, many

universities are improving their outdoor spaces for seating and some are

creating outdoor learning environments,” Florio said.

These kinds of

measures may help ease some of the concerns students have about returning.

According to a survey released in August by higher education research and

marketing firm SimpsonScarborough, just 25% of returning college students feel

strongly that their schools would take the necessary safety precautions to

protect them from COVID-19. Three-quarters of incoming freshmen are worried

they will contract COVID-19, and only 34% of returning students feel safe

living in residence halls. As a result, 40% of incoming freshmen interested in

four-year residential colleges say they will likely not attend in the fall, and

28% of returning students may not come back to campus either. Addressing safety

concerns will be critical for educating millions of students, and for ensuring

the success of academic institutions as businesses.

Monitoring Safety

To create a safer

learning environment, risk managers should build on the best practices they

have already developed. Start with basics like threats to revenue, reputation

and compliance. From there, Holland said, “identify those risk topics where you

think you can truly help the institution succeed and move forward with its

strategic goals.”

One of those topics

may be how students at the K-12 level will get to school. Bus operations will

have to change as physical distancing protocols will likely reduce the number

of students allowed on each bus. In addition, students may have to wear a mask

and board the bus from the back to fill seats while minimizing exposure,

Gjerdrum said.

Bus schedules may

also have to change. Some districts, for example, are considering splitting the

school day into morning and afternoon sessions to allow students to attend

in-person classes at least part of the week, she said. That would require

additional buses to run more frequently during the day to accommodate multiple

rounds of pick-up and drop-off, adhere to capacity limitations, and allow time

for cleaning between trips.

Once in school,

students will need to distance as much as possible. Gjerdrum recommended having

fewer students per class and keeping students in the same room. “That way, if

someone in the group gets sick, you can isolate that group,” she said.

Voluntary health

screening processes can help assess whether students are sick and may be useful

in limiting spread of the virus. Holland said the University of Arizona is

using an app that allows the university to track students through methods like

logging Wi-Fi access. The opt-in technology allows for quick notification of a

student’s exposure to someone who has tested positive, also referred to as

contact tracing. “If I become COVID-positive, public health authorities have

access to a database that would say you were in the same restaurant at the same

time I was,” Holland said. “They may then reach out to you to see if you’re

having symptoms.”

His campus is also

adopting daily health screening in the form of a text-based questionnaire that

asks users to answer questions about symptoms like fever. The technology clears

healthy people to go to school and sends information on treatment options to

people with symptoms, Holland said.

While helpful, such

health screenings are not foolproof. That is why Holland believes following

health guidelines, such as requiring mask use, is critical to reducing the

spread on campus and in classrooms. His institution is empowering faculty to

enforce compliance. “If you have a student who refuses to wear a mask, and they

don’t have a medical basis or an accommodation reason why they can’t wear it,

you need to have the authority to tell them they can’t be in your class,” he

said.

Guideline

enforcement and wellness checks are especially important for the most at-risk

segment of a school’s population: faculty and staff. Schools should support

their employees and find the best work arrangements to ensure their safety. “If

they feel they’re not comfortable or able to come back to work, we want to

support that and help them get through that process,” Florio said.

Many institutions

are allowing administrators to work from home when they are able, and allowing

faculty to teach in the way that makes the most sense for them. Some may have

family members at home with conditions that put them at higher risk. When

building any plans for reopening, risk professionals should be understanding of

such needs and should consider the potential harm that could result from each

course of action.

According to

Holland, rethinking how learning can take place safely will prove especially

critical if campuses must close again. Making any decisions about closures will

require ongoing monitoring. To that end, his team is working on identifying

different stages of response based on the status of the pandemic in the

community. “We’re identifying metrics that we want to watch over time, like the

number of new cases, and we’re identifying close contacts when we have a person

who reports a positive case, and what percentage of those close contacts also

develop symptoms or end up testing positive for COVID,” he said. This will help

them adjust procedures and protocols as necessary.

All About Balance

The balancing act

between traditional classroom instruction and the health of students, faculty

and staff is actually not so far outside of normal risk management practices.

Institutions that have adopted robust enterprise risk management practices are

best prepared to handle pandemic-specific issues, Clark said. However, too many

institutions will struggle, particularly at the college level. Many will have

to play catch-up with ERM, which could put them behind the curve in terms of

being prepared for pandemic-related issues. “It has been a real eye-opening

moment for higher education risk managers, and shined a spotlight on the

importance of developing a true enterprise approach to risk,” he said.

Amid it all, risk

managers still have to perform the same tasks they did prior to the pandemic.

That is where establishing an oversight team to handle pandemic-related issues

could be beneficial. Bennett suggested the team should comprise key

participants from health services, housing, facilities, academic affairs and

communications departments in addition to risk management and legal counsel.

“There will be sub-teams under that doing a lot of the work, but you need that

oversight group watching everything that is happening,” she said.

Communication and

information-sharing among risk professionals at different institutions will be

critical to the success of new practices. “Risk managers are really overwhelmed

this year with the amount they have to do and the amount of information coming

in,” Bennett said. “The more that we can talk to each other and tell each other

about the best practices that we’re seeing and experiencing, that is going to

be really helpful this year.”