This post first appeared on Risk Management Magazine. Read the original article.

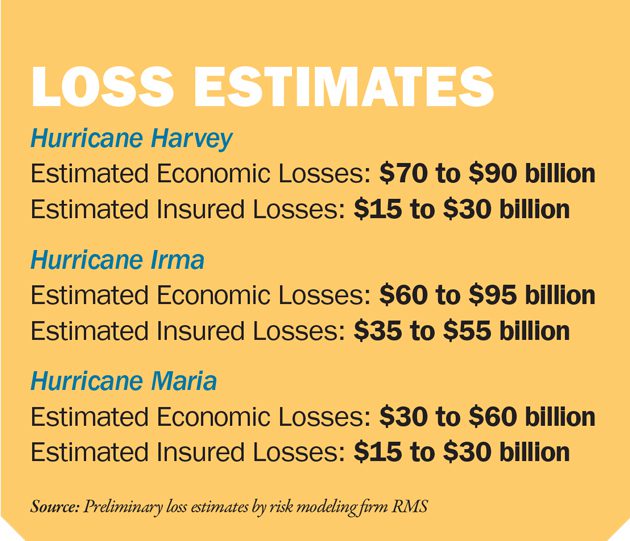

A devastating hurricane season left catastrophic damage across the Atlantic basin, with the most severe storms in more than a decade striking the Caribbean and southern United States in close succession. While the year is not yet over, 2017 is already one of the most expensive in history for natural disasters. Risk Management spoke with individuals from across the risk and insurance community who were involved in the season’s three major Atlantic hurricanes—Harvey, Irma and Maria—to discuss their first-hand experience weathering the storms, managing disaster response and recovering in their wake.

A devastating hurricane season left catastrophic damage across the Atlantic basin, with the most severe storms in more than a decade striking the Caribbean and southern United States in close succession. While the year is not yet over, 2017 is already one of the most expensive in history for natural disasters. Risk Management spoke with individuals from across the risk and insurance community who were involved in the season’s three major Atlantic hurricanes—Harvey, Irma and Maria—to discuss their first-hand experience weathering the storms, managing disaster response and recovering in their wake.

✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺

Doug Backes

Global Vice President of Claims, FM Global

You just got back from working with your claims team in Puerto Rico—what was it like on the ground?

It’s not like anything I’ve seen in almost 25 years. The devastation is really catastrophic. It looks like Armageddon, to be honest. Once you get out of San Juan, the devastation becomes even more apparent. You see downed power lines just about everywhere. They have concrete power poles and many have just snapped right in half. It was not a small storm by any stretch of the imagination.

The impact from a business interruption standpoint is going to be amazing, particularly in that, if you don’t have the ability to continue operations through your own energy source—if you’re not generating electricity for yourself—you’re really out of business right now.

Are there any measures that particularly helped define which of your clients best weathered the storm?

You really see, in action, the business continuity planning that clients have in place. In one day, I tagged along with a claims adjuster to visit a client that had several buildings with roof coverings off, sub-grade areas full of water, mold growing on the walls, and they’re doing everything they can to try to rein that in, to protect themselves and dry things up and get the environment stabilized, while also trying to keep clients or customers satisfied. They’re limping along the best they can, but it’s a mess. That afternoon, we visited another client that had invested a large amount of money in storm-hardening and electrical generation capabilities, and when we toured that facility, the business is running, the environment is stable; they’re putting the perimeter fence back. I’m not minimizing what happened to them, but three weeks after the event, these folks were back to (somewhat) business as normal, whereas the folks earlier in the day were scraping just to get themselves dried up.

What do you expect will pose the most difficult challenge in recovering from Maria?

The infrastructure. If you’ve invested money to protect your facilities from this type of storm—160 or 180 mile-per-hour wind—you may have made it through largely unscathed, but still may not have electricity, cell service, or water or sewer because you’re relying on the infrastructure. That can create insurance issues. Damage and business interruption from the damage is one thing, but once you’re back in business or could be back in business, if you’re still waiting on the grid to come back, that’s largely what we call a “service interruption event” and, under most policies, that is typically an additional coverage and may have a sublimit. The island is also in financial difficulty, and delays due to things like that are typically not insured.

How long do you expect it will take to restore electrical infrastructure?

We’re currently estimating six months, but the more we see, the more I get the sinking feeling that that’s an optimistic bet—it could be six months to a year.

I imagine that means you expect significant business interruption losses as well?

I think the impact from a business interruption standpoint is going to be amazing, particularly in that, if you don’t have the ability to continue operations through your own energy source—if you’re not generating electricity for yourself—you’re really out of business right now.

Almost all cell towers were destroyed as well—is that an issue your clients planned for?

Once you get out of the downtown area in San Juan, there is virtually no cell service, so communicating with your family or your business or your corporate offices is a problem. On the highways, you can be driving along and all of a sudden you come to a stop because a bunch of cars have pulled over on a bridge—their cellphones have pinged, meaning they’ve got a signal, so they pull over so they can make phone calls. That infrastructure has got to be restored. Many of our clients have established service on their properties, such as through satellite dishes, to make sure they’ve got a reliable means of communication with the outside world.

Was business continuity planning adequate for such a severe storm?

We’re finding that companies with corporate operations off the island tend to be more resilient. Puerto Rico isn’t a mystery—it’s a high-hazard zone for earthquake and a high-hazard zone for wind. Those are not unknown factors. Whether it’s a retail store or a high-tech pharmaceutical operation, businesses can build supplier emergency stacks and store supplies of their inventory off the island, then utilize those inventories during the storm or their downtime so that, when they do resume operations, there hasn’t been as huge a sales impact. But short of that, if you have not done some pre-loss planning, you’re really grasping at straws once the damage from an event like this has happened.

✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺

Lance Ewing

Executive Vice President of Risk Management and Client Services, Cotton Holdings

Working for a disaster recovery and restoration services provider, you’re in the unique position of having spent time on the ground after each of this year’s hurricanes—Harvey, Irma, Maria, Lidia and Nate. Which did you find the worst?

Maria was probably the worst because of the ongoing situation in Puerto Rico. From a flooding standpoint, Harvey was the worst flooding I’ve ever seen, other than in Asia. It was just of epic proportions.

How was the disaster response in Houston?

I have to say, they are in some ways more well-prepared for it. From a risk resiliency standpoint, they certainly stepped up. Now, they also got some outside help, which was good, and FEMA was quicker to respond with the National Guard, and I think not evacuating was probably a very smart move by the Houston mayor. You also had groups from outside, like the Cajun Navy, coming and helping, and you really saw a lot of human kindness step in.

Things like emergency generators were in very short supply and, in some cases, continue to be in short supply. A lot of them went to Harvey and they had to flex and go to Florida for Irma and they had to flex again and go to Puerto Rico—there’s not an endless supply of the emergency response equipment that corporations need, and even if we can find them, it might be a couple of days before we can physically get to your facility.

What did you think of the response to Maria on the ground in Puerto Rico?

Maria really lasered in on Puerto Rico and I think the preparedness was not as strong as in other places. The federal government, in my opinion, responded as quickly as they could, but there are a lot of logistical issues people do not see if they aren’t down in the weeds. For example, if you want to bring all those supplies in, you need labor to unload them. You think local labor would do that, but they couldn’t because they were dealing with their own problems at home or they couldn’t get there. You could bring people in, but when you think about outside laborers, you need to be sensitive—are you taking jobs and wages away from individuals who are there and need it most? It’s a delicate balance.

Did you see any major differences in the recovery processes from these storms?

The response in Houston had a lot of thought to it because there was more collaboration between city, local, state, federal and then outside organizations and the National Guard. And with the flooding, you knew in the back of your mind that the water was eventually going to recede. But in Maria, you have the wind damage, the flooding, getting equipment there, and the power grid situation… Electricity was up and running in a number of areas in Houston, which made life a lot easier. When you’re looking at the differentiation between the two, Houston has mostly bounced back already. You don’t see that in Puerto Rico because, I think, of the power issues. Government, infrastructure resiliency and business continuity planning have got to step up.

Were there any common issues you saw among the continental hurricanes?

Throughout Hurricane Harvey and specifically in the Florida area with Irma, one common thread was that people and corporations were looking for immediate response from their insurance carrier, from their adjuster, from their remediation services, and patience sort of lacked. It was kind of “why can’t you be there right now?” Well, if the roads are closed, you can’t get the equipment or adjusters in. There is an issue in the sort of patience meter and instant gratification in incident response. Corporations may need to start building that into their business continuity plan, including some self-resiliency.

What was the hardest challenge for you in handling so many natural catastrophes so close together?

It’s probably the volume of people adversely effected and trying to prioritize the depth and the breadth of what they really need, then finding and providing those resources. Things like emergency generators were in very short supply and, in some cases, continue to be in short supply. A lot of them went to Harvey and they had to flex and go to Florida for Irma and they had to flex again and go to Puerto Rico—there’s not an endless supply of the emergency response equipment that corporations need, and even if we can find them, it might be a couple of days before we can physically get to your facility. Or if we can get the generator there, there may be nowhere to set it up because you can’t put it in six feet of water—you have to wait for the waters to recede. That comes back to patience.

✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺

Michelle Bennett

Director of Risk Management, Cable One

Most of the impact your company faced was from Harvey—what are your primary losses?

At least 70% of our claim is probably the business interruption and contingent business interruption, suspension of billing, customers that go away, all our market disappearance…and how long the insurance company pays for that, I don’t know. Especially if you’re a service provider, after a certain period, many property programs just don’t cover market disappearance, which is understandable because your period of indemnity is what it is. But how do you plan for that? That is a takeaway we’re going to examine as we recover and get our lessons-learned in place.

I think that brokers and insurers have been unusually taxed from a resource perspective and I can see that there is a talent shortage in the world of claims. I didn’t perceive that before, because you had enough people to go around. Now, I have concerns that the available talent in that advocacy pool is dwindling.

How much of that is contingent business interruption?

It could very well be 30% to 40% of the total BI number. We didn’t suffer a lot of damage and didn’t have to call in a bunch of expensive resources for repairs or replacement. We had our service ready to get back to the customer, and commercial power was up fairly quickly where we were hit, but if somebody doesn’t have a home, they’re certainly not going to want their internet service back on. And if it takes six months to rebuild…there’s no way for us to estimate that right now. Reputationally speaking, we had to do the right thing—it’s a disaster zone, we’re not going to continue billing somebody who can’t use our service. I haven’t crossed that bridge just yet with the insurer and I am very curious to see their response to that decision.

Are there any other strategic financial choices you have made in the recovery process?

We spent a little extra to get and retain specialized contractors to do repairs and minimize the loss. With all of the disasters that are happening, contractors are being pulled in a lot of different directions to make the most money, so we offered creature comforts like a shower trailer. It was an expensive shower trailer, but it helped us keep contractors more than we ordinarily would have been able to, and in an indirect way, it actually saved money. And that is the argument I will make to our insurer.

In such a grueling year for catastrophes, have you encountered any challenges with availability of recovery services or your insurance company?

With this highly active season, I’ve noticed the taxing of resources—not just from service providers, but also as an insured, in the adjustment process and from an advocacy and expertise standpoint. It’s often feast or famine with these kinds of storms, but I think that brokers and insurers have been unusually taxed from a resource perspective and I can see that there is a talent shortage in the world of claims. I didn’t perceive that before, because you had enough people to go around. Now, I have concerns that the available talent in that advocacy pool is dwindling.

Has that shortage led you to feel pressure from within your organization while navigating the claims process?

I’ve been feeling pressure internally mainly because it’s coming at an interesting time. Now, we’ve got the quarterly earnings calls and there is pressure to have some sort of recovery in place by the end of the year because that affects our revenue and hitting certain targets.

Did your contingency or disaster response planning otherwise hold up?

That’s a difficult question to answer because we don’t have detailed, formalized plans. So what we had was somewhat reactionary in nature and we relied a bit on muscle memory of folks who have been here for a long time. I think we got through it really well, all things considered.

Moving forward, will you be creating a more formal plan?

Oh, absolutely. But it’s just me, myself and I. Culturally speaking, it’s difficult to get the resources and bodies in time to address something that extensive, because you’re not just talking about having an emergency response plan or a crisis management plan, you’re talking about doing business impact analysis and organizing disaster recovery plans with the IT and IS departments. That is a much broader scope and it takes time and money.

✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺ ✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺

Elizabeth Guimaraes

Director of Risk Management, Nova Southeastern University

The university has campuses in both Florida and Puerto Rico, so you have experienced both Irma and Maria—how did you fare?

There is damage, but overall Irma has been more of a nuisance—leaking roofs and debris that has only seemed to grow rather than go down in the month since, but thankfully no wholesale flooding. The main campus was closed for about 10 days to ensure there was no severe damage. In Puerto Rico, we lease, we don’t own, and we were fortunate the building was built to much stronger, stricter standards than most. There are roof leaks and windows blown out, so we certainly have contents damage, but compared to what you see across the island, the damage was not catastrophic. Unfortunately, the problem is everything else that comes along with having property and operations in Puerto Rico, like having a stable power grid. Our particular location happens to be on a hospital grid, so we got power back fairly quickly, however, even for those that do have it, the power grid is very unstable.

It’s the infrastructure and not being able to control that piece of it that’s really causing the struggle and concern. Many people have pointed out, as it is an island, it’s not like you can just grab a truck—you’ve got to barge stuff in or fly it in. And with so many roads out of commission, trying to get supplies or anything across the island is also a massive undertaking.

What is your biggest challenge in responding to Maria?

It’s the infrastructure and not being able to control that piece of it that’s really causing the struggle and concern. Many people have pointed out, as it is an island, it’s not like you can just grab a truck—you’ve got to barge stuff in or fly it in. And with so many roads out of commission, trying to get supplies or anything across the island is also a massive undertaking. The isolation, I think, has added to the angst for everyone because of the difficulty of not being able to move faster with what we need to do and want to do for our community.

How have you managed such fundamental problems?

At the end of September, a foundation provided a very large donation for our medical programs. When the storm hit and we were obviously concerned about all of those supply and transportation issues, this particular benefactor was extremely generous and provided his jet to allow some of our personnel to fly to the island. They have made quite a number of trips to take water, food and supplies, then stage them at our location in Puerto Rico and get the message out to faculty, staff and students so that they know we’ve got those things to try to assist them.

How have students and faculty been impacted?

Some of the students evacuated, but most of them live there and remained, and many are now dealing with the stuff you see on the news: no reliable water source, gas shortages, a curfew on the island. With most electricity still out, most intersections have no power, so for example, if we kept the campus open too late, there was concern that people were driving in utter darkness. It all affects people being able to come to classes or to work on a regular basis.

Between electricity and physical access, has it been difficult to get recovery services in and repairs done?

Many of the service providers are very busy. Part of the issue has been just getting supplies—FEMA was only allowing in flights and ships that were providing basic needs like food, water and regular supplies, so even when some of the service providers were available, there were no materials for the repairs. Some are also trying to get work done with a limited number of employees, because of the transit issues and their recovery at home. They also had a lot of rain [at the beginning of October], so you kind of took one step forward and two steps back in a lot of places.

How did your disaster response and business continuity planning hold up in practice?

Thankfully the university had its own emergency plan and, for the most part, it responded very well. Once the storm season is over and things settle down, we will have a much larger discussion to check for any holes and see how we can respond quicker. We hope we never see another hurricane season like this one, but unfortunately I don’t think we’re going to be that lucky.